View entry

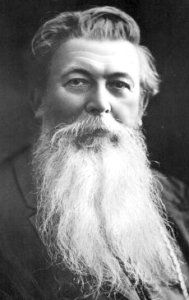

Name: LE ROY, Alexander Louis Victor Aime (Father)

Birth Date: 19.1.1854 St Sénier-de-Beuvron, Manches

Death Date: 21.4.1938 Paris

First Date: 1881

Profession: Holy Ghost Fathers - Zanzibar Mission; dep. Zanzibar for Lamu 2/11/1889, dep. Lamu for River Tana to establish mission at Ndera 27/11/1889; after trip up Sabaki arr Zanzibar 28/1/1890

Area: Zanzibar

Book Reference: North, Nicholls, Mombasa Mission, Baur

General Information:

The situation changed dramatically when he was able to replace ailing confreres in other missions and to accompany Fr. Baur or Bp. de Courmont on exploratory trips to determine the best locations for the missions. A keen observer of the land, its people and their customs, and endowed with a fertile pen, he wrote numerous articles and several books about his travels that were widely read by the public at large. He also felt at ease with African people, whatever the tribe to which they belonged, and could converse freely with them. Moreover, he had a good grasp of what ought to be done. For example, when he was stationed in Bagamoyo and noticed that a slave mentality still existed among the young people who worked for the mission, he simply stopped the system of providing them with all they needed and demanding that they work for the mission; he replaced it by setting them "free': from now on they would grow their own food, maintain their own huts, and work for wages in the mission or elsewhere to eam a living in the system. It stopped all the abuses that had crept into the system. We may relate here a story showing Le Roy's wit even in a trying situation. On one of his trips he was sent to Morogoro to replace the ailing priest stationed there, but he himself also became seriously ill. Expecting death, the two priests anointed each other. Then the other priest died while Le Roy seemed to be in a coma. The one Brother in the mission made a coffin, conducted the funeral and then retumed to the house. Looking at Fr. Le Roy, he thought that this one was also dead and muttered, "Darn it! l'll have to do it all over again. lt is disgusting, but I do not even have another packing case to make a coffin for him." Whereupon the would-be corpse replied: "why don't you use a sack?" Anyhow, he recovered and could return to Zanzibar.

His explorations were not limited to what had become German East Africa, but extended into British territory in Kenya, where he penetrated as far as Malindi and became acquainted with Pygmies [there are no pygmies in Malindi]. He also climbed Mount Kilimanjaro up to 16,500 feet and laid the foundations for the evangelization of the Chagga people. His description of that trip reached many, including an avid former mountain climber better known as Pope Pius Xl (1922-1939). Years later, when he was received in audience by this Pope, he heard him say: "l followed you up all the way on Mount Kilimanjaro." On this trip he also became acquainted with the nomadic Maasai: they received him very graciously and impressed him as a splendid people who would be a great asset to the faith if they were to accept Christianity. Le Roy would have loved to stay on in that area for the remainder of his life. But it was not to be. ln 1892, after nearly 11 years in Africa, the Holy See named him vicar apostolic of Gabon on the West Coast of the continent. Ordained a bishop on October 9, 1892 at Coutances, he arrived in Libreville on March 19, 1893. He visited and reorganized the missions and founded several new ones, introduced the system of catechists-he even got official permission to associate married catechists with the Congregation as a kind of Third Order-and opened a seminary that would produce several African priests.

ln 1896 this phase of his life came to an end when he was elected Superior General of the Congregation. As such, he reorganized it into provinces and work districts, laid the foundation for new provinces in Belgium, the Netherlands, England, Switzerland and Poland, saw the Spiritans expelled from Portugal in 1910 but readmitted again in the 1920s, and in 1904 managed to convince the highest court in France that the executive government of the country did not have the power to expel the Congregation; only a new law of the legislative branch could do so. ln this way he saved the Generalate and the Province of France from having to go into total exile, even though numerous colleges and schools had to be given up and he had to find suitable positions for the 300 Fathers and Brothers working in them. ln preparing that lawsuit before the supreme court he also found out that he was not the fifth but the fifteenth superior general of the Congregation.

He remained Superior General for thirty years playing a crucial role in many events. He saw 600 members of the Congregation mobilized for World War One, and 124 of these lose their lives. Remarkably enough, among the survivors only two scholastics and three Brothers did not retum to the ranks of the Congregation. He saw the institute flourish and expand and its missions growth beyond all expectations; he also founded in 1924 the missionary Sisters of the Holy Spirit. Feeling old and seriously ailing, he resigned in 1926. On the golden anniversary of his ordination in the same year, the Holy See raised him to the rank of an archbishop in recognition for his tremendous work. Once he had resigned, however, his health improved considerably and for another decade he could continue to write. Finally, twelve years after his resignation, his weakened heart could no longer carry on and he passed away peacefully.