View entry

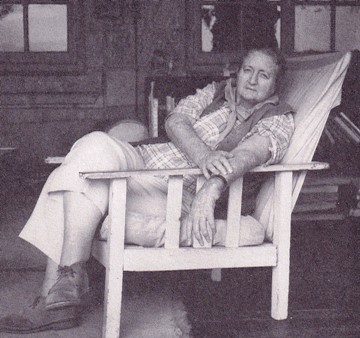

Name: SCOTT, Pamela Violet Montagu-Douglas-

Nee: dau of Lord Francis Scott

Birth Date: 7 July 1916 Wandsworth, London

Death Date: 5 Feb 1992 Rongai

First Date: 1930

Last Date: 1992

Profession: Farm manager

Area: Deloraine Estate, Rongai

Married: no

Author: A Nice Place to Live, 1991

Book Reference: Hut, Debrett, Charters, Habari

General Information:

Charters - Nakuru - Miss Pamela Scott …… never hesitated to drive African patients to Nakuru (a distance of over 20 miles on a rough earth road) at any hour of the day or night.

Habari - Pamela Scott, who has died aged 75, hailed from the pinnacle of the aristocracy as a granddaughter of the 6th Duke of Buccleuch, but whereas her remote ancestors had expended their energies upon cattle thieving in the Borders, she brought her native toughness and resilience to bear upon running the family estate in Kenya. It was in 1934, when she was only 18, and fresh from the London season, that her father, Lord Francis Scott, who wanted to devote himself to Kenya politics, made her manager of the 3,500 acre property at Rongai. The family home, Deloraine, was vast, but the conditions of life were primitive. Water for the farm had to be carried over 2 miles, while the railway was some 20 miles away. Pamela Scott, entirely without expert help, perforce relied on trial and error to learn the arcane arts of animal husbandry - castration, dehorning, branding, calving and rearing. All work on the farm came within her ambit; she studied accounting, undertook building and fencing, put down metalled roads, constructed dams - even on occasions acted as midwife.

The struggles and hardships of the life were strangely at odds with her pedigree. Miss Scott was often at the ends of her financial tether, yet after her cousin, Lady Alice, married the Duke of Gloucester in 1935, the indigent farmer received clothes that had been used for state occasions. Pamela Scott's resource never failed. When one of her workers began to wither away after being put under a witchdoctor's spell, she concocted an antidote consisting largely of kerosene, scent, and Eno's fruit salts - which proved entirely successful, if somewhat violent, in ejecting the evil spirits. Her family had never encouraged sentimentality. "You're a damn fool, woman" her crippled father would yell, while lunging at her with his stick - yet she judged him "the kindest of men."

She admitted some nervousness when attending London dinner parties as a girl, but in the real world nothing daunted her. Informed on one occasion that a drug-crazed native was coming up to the house with the intention of butchering her, she stood her ground and trapped him in the cellar. During the Mau Mau terror in the 1950's, when so many Europeans barricaded themselves in their houses, Miss Scott left Deloraine open as usual. Her precautions consisted of arming herself with a Beretta pistol and putting a Masai on the veranda, so that his shrieks might give warning in case of attack. In the last analysis her best security lay in her work for the Africans. Over 45 years her management of the farm yielded extraordinary achievements. She started with only 17 cows; in 1979 there were 1700 cattle. By the time she retired the farm was run entirely by Africans. The estate had become a flourishing community of more than a thousand people. Miss Scott had established a school on the farm which grew to take 300 children, some of whom went on to further education. A few of them even reached universities in Europe and America; the alumni of Deloraine included an architect, civil servants, nurses and journalists.

It was no wonder that Miss Scott showed impatience at the image of decadence among white Kenyans purveyed [sic] in James Fox's book "White Mischief". She would point out that the 'Happy Valley' set represented perhaps a dozen people out of 40,000 settlers. Lord Francis Scott, Pamela's father, had emigrated to Kenya after the First World War. For all the rigours of the pioneering life, the Scotts remained a magnet for visiting dignitaries. In 1924 the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) came to stay, and Pamela remembered being upset at having temporarily to forfeit her pony to the Duchess. Four years later the visit of the Prince of Wales caused her fewer problems, even if the Prince distinguished himself in Nairobi by rolling about on the floor of the Muthaiga Club with Lady Delamere.

Her education was a sketchy affair, as her parents took the view that examinations made a child narrow-minded. Few of the governesses who came to Deloraine lasted the pace. Her childhood was interspersed by visits to England, during which she would make the rounds of the Buccleuch seats. When Queen Mary invited Pamela to tea the girl inquired whether she had diamonds on her sponge. The Queen, always severely practical, replied that she had not; they would be very scratchy. At 15, Pamela was sent to boarding school at Downe House, near Newbury, which she loathed. Subsequent skirmishes with learning occurred in Paris and Devon. But her heart was always in Africa.

Her father had taught her to ride on the principle that no one could be any good until they had fallen 50 times; as a result of which she became a fine horsewoman, and an enthusiast of the turf. For all her educational deficiencies, Miss Scott possessed a stern capacity for self-control - she was, for example, a rigorous teetotaller - which enabled her to succeed in all she attempted. But she inherited to the full her family's suspicion of intellectuals. When Cyril Connolly went to stay at Deloraine she introduced him as "John O'Connor" and did not conceal her exasperation when that literary luminary sulked. "He might as well not have been there" she complained. The kind of man that Pamela Scott admired was one who could break a horse, calve a cow, or overhaul a tractor. Even so, when dancing with farm managers in Nairobi, her mind would turn to more primitive entertainment, to the Masai warriors leaping up and down to a slow chant under the stars. She was interested in African history, customs and languages, though she berated herself for talking Kiswahili "like an uneducated yokel". The phrase reflected her aristocratic disdain for distinctions of race or education.

It was natural for her to find an English equivalent to the Masai initiation ceremonies [including female circumcision] which she witnessed. "I suppose all this business ….. Gave them confidence and made them self-reliant, which is very much what my season in London had been meant to do for me. Equally, while other whites went on about the horror of Mau Mau atrocities, she would reflect that only about 30 Europeans had been killed, whereas some 10,000 Kikuyu perished. In 1962, when so many settlers, fearful of black rule, were leaving Kenya, Miss Scott expanded her landholding by purchasing the farm next door. After independence, which came next year, she was one of the first Europeans to take citizenship of the new country. She actually preferred the African regime to colonial society. Her work on agricultural committees continued; she became a member of the board of governors of Egerton Agricultural College and she helped to raise funds for a secondary school.

In 1979 she sold her farm to the Rift Valley College of Science and Technology, although she stayed on in the house and rented back some 60 acres for cattle. Perhaps her best epitaph was spoken by Daniel Arap Moi, the President of Kenya: "This one looks white, but she is black at heart." Pamela Scott's memoirs, "A Nice Place to Live" offer many fascinating insights on life in Kenya and on her own admirable character. "I remember her as a strikingly beautiful young woman," said one of her male contemporaries, "but it was not advisable to take liberties." She never married.