View entry

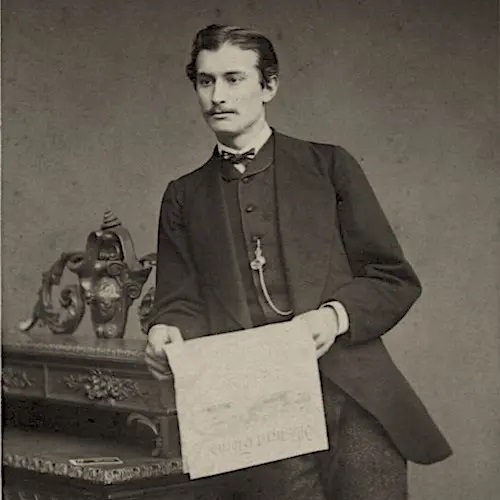

Name: SCAVENIUS, Peder Bronnum 'Peter'

Nee: initials given as 'N.B.'

Birth Date: 12 Apr 1866 Pa Gjorslev Slot, Denmark

Death Date: 27 Mar 1949 Copenhagen

First Date: 1894

Last Date: 1894

Profession: One of the controversial 'Freelanders'. Son of a Danish cabinet minister

Area: Lamu

Married: 1. Catharina de Grinewsky b. 5 Apr 1866, d. 18 June 1923 (later m. Pierre de Kataley); 3. Emma Andrea Fernanda Mourier-Petersen b. 16 Apr 1871, d. 13 June 1957; 3. Alvilda Rasmussen b. 14 July 1880, d. 29 July 1944

Children: 2. Marie Louise Alvilda (Briand de Creve) (17 Feb 1897 Denmark-7 Jan 1978 Malaga, Spain); ; Elisabeth Anna Charlotte Sophie (Hartz) (28 Oct 1898 Denmark-19 Mar 1962 Randers Amt, Denmark)

Book Reference: Freeland, North

General Information:

North - International Freeland Assoc.; former Midshipman with Danish Navy; initials sometimes given as "N.B."; aged 28 arr. Lamu 2/4/1894

North - Assoc. disbanded at Lamu 25/6/1894; Had left Lamu by July 1894; "Intriguing agitator, bitterly hostile to British influence" (Dugmore, FO 403)

lizadaly.com/pages/utopian-novels/freeland Son of a wealthy Danish landowner and politician, at the time of the expedition Scavenius was a 28-year old former merchant marine. He published his account in The Freeland Expedition: Its Origin, Course, and Downfall just three years after the event....Scavenius saved his greatest scorn for the “intolerable” condition of Freeland House. There was no indoor plumbing and on-site toilets were just two holes in the masonry floor that led to a cavity under the living space; the smell seeped up into the sleeping quarters, which he also hated. “Mattresses were considered an unnecessary luxury for the Freeland expedition, and the dormitories stank like a hospital with gangrene patients.” There were no chamber pots either, so the Europeans’ “great merry sport” was to urinate out of the upper-storey windows onto passing Africans, whose curses provoked laughter among the Freelanders. The city’s natives asked in turn whether there had been a great famine or rebellion in Europe which forced these sad, dirty, drunk men to invade their island. Scavenius remarked that officials were “all too aware that the British reputation with the indigenous people of the region was suffering by the presence of this whole gang of shabby-looking people without a dime in their pockets.”...

On May 21, 1894, the ultimatum from British officials came: if the Freelanders could not begin their expedition immediately, they would have to return home. There was simply no money of that scale available; what Wilhelm had received for all his entreaties was a fraction of what was needed. “The rain whipped throughout the day in torrents,” Scavenius recalled, “and transformed the narrow streets into tearing, dirty-yellow streams. It penetrated through the surface of the barracks, leaky roofs, and filled the filthy camp beds of the Freelanders.” It continued to pour into the house all through the tense breakfast meeting—Wilhelm told servants to fetch him a new plate four times as it kept filling with rainwater.

Wilhelm, by fiat, announced that the Freeland Expedition was at an end—this formality mattered to him because it marked the cessation of his fiscal and reputational responsibility for the group. He blamed Hertzka for failing to provide adequate funds (though in a letter to Hertzka, he would blame British officials for stonewalling them instead) and told everyone they should pursue their own prospects from here on out.

On May 21, 1894, the ultimatum from British officials came: if the Freelanders could not begin their expedition immediately, they would have to return home. There was simply no money of that scale available; what Wilhelm had received for all his entreaties was a fraction of what was needed. “The rain whipped throughout the day in torrents,” Scavenius recalled, “and transformed the narrow streets into tearing, dirty-yellow streams. It penetrated through the surface of the barracks, leaky roofs, and filled the filthy camp beds of the Freelanders.” It continued to pour into the house all through the tense breakfast meeting—Wilhelm told servants to fetch him a new plate four times as it kept filling with rainwater.

Wilhelm, by fiat, announced that the Freeland Expedition was at an end—this formality mattered to him because it marked the cessation of his fiscal and reputational responsibility for the group. He blamed Hertzka for failing to provide adequate funds (though in a letter to Hertzka, he would blame British officials for stonewalling them instead) and told everyone they should pursue their own prospects from here on out.

Addressing the group only in German, he suggested a postscript—a brief exploratory expedition up the Tana before they departed, so they could say they got something out of the whole sorry deal, and promised to use his personal family fortune to fund it. “We could not get out of our heads that Wilhelm had a very rich father, so we listened to his siren song,” Scavenius wrote.

The Englishmen, puzzled by the sudden change in tone, waited for someone to translate, and then erupted in protest: British officials had granted permission only for the British Freeland Association expedition, not some ad hoc safari led by Austrians and Germans, and they immediately left to inform on the group. Scavenius noted astutely that on that day, everyone believed they were victorious—the British, because surely the expedition was now over, and the Germans, because they saw themselves as finally taking control.

Scavenius continued to travel extensively but never returned to Africa. He would marry four times, the last when he was 80 years old. He died in Copenhagen in 1949.

The Englishmen, puzzled by the sudden change in tone, waited for someone to translate, and then erupted in protest: British officials had granted permission only for the British Freeland Association expedition, not some ad hoc safari led by Austrians and Germans, and they immediately left to inform on the group. Scavenius noted astutely that on that day, everyone believed they were victorious—the British, because surely the expedition was now over, and the Germans, because they saw themselves as finally taking control.

Scavenius continued to travel extensively but never returned to Africa. He would marry four times, the last when he was 80 years old. He died in Copenhagen in 1949.